Observations on Obstetrics and EBM

We live in the age of evidence-based medicine and an increasing willingness on the part of patients to review medical guidance and actively participate in their care. This includes such personal and emotional areas like pregnancy and birth. Some popular tools to help would-be parents include Emily Oster’s famous “Expecting Better” and evidencebasedbirth.com.

We’ve had our fourth child this year and each time we go through prenatal appointments, birth, and post-partum care I encounter some differences between recommendations I’ve found in the literature and what providers say or do. It sticks out to me more than other branches of medicine I’ve encountered, but that might just be a difference in the amount of experience I’ve had versus willingness to go on Google Scholar for a lit review due to personal nature of the topic. Either way, in this post I wanted to share some notes on two particular issues that I’ve encountered and what I’ve seen in the literature on those topics. Obviously I’m not a medical provider and this is not medical advice, just a literature review by a curious statistician.

Table of Contents

Low Amniotic Fluid Volume (AFV)

When your little baby is in utero it is surrounded by amniotic fluid. A sufficient amount of amniotic fluid is important for the baby, as it provides a cushion and allows for nutrient and oxygen flow through the umbilical cord. When amniotic fluid levels are low, baby’s ability to receive nutrients and oxygen can be hindered. This is called oligohydramnios in the literature.

It is important to know that we can divide cases of low amniotic fluid volume (AFV) into two broad categories:

- the idiopathic, that is cases where no explanation for the low fluid level is known. it happens “on its own;” this is also called isolated oligohydramnios. This is the most common.

- low AFV as a side effect of another pregnancy complication. This can be further divided into maternal causes, i.e. a complication arising in the mother, the fetus, or having a placental cause.

See the StatPearls article for relevant citations on these categories. This post focuses on idiopathic oligohydramnios, or isolated oligohydramnios (IO).

Measurement Techniques

How is IO diagnosed? Accurately measuring AFV is difficult. The most accurate technique is invasive and involves injecting a dye into the amniotic cavity and sampling of the amniotic fluid to determine a dilution curve. This technique is accurate but impractical, so most AFV assessments during pregnancy are done via ultrasound measurements. Two techniques have been developed: the amniotic fluid index (AFI) and the maximum vertical pocket (MVP) technique, sometimes called single deepest pocket (SDP).

For MVP, a sonogropher identifies the deepest pocket of amniotic fluid not including the umbilical cord or body parts and measures the length from the 12 o’clock to the 6 o’clock position. The normal range is 2-8 cm, with <2 cm diagnosed as oligohydramnios and >8 cm as polyhydramnios. For the AFI method, the uterus is divided into 4 quadrants and the MVP is obtained in each quadrant. A sum of less than 5 cm is diagnosed as oligohydramnios (Keilman and Shanks 2022).

There is a long debate on which method is better, but a Cochrane review of five trials suggested providers use MVP as opposed to AFI due to an increased number labor inductions and Ceasarean deliveries among women screened using AFI, with no concomitant improvement in perinatal outcomes (Nabhan and Abdelmoula 2008). As of 2014, ACOG followed suit and recommends the MVP method (Landon et al. 2018). But a decade later many providers continue to rely on the AFI. That was my experience with our providers in fetal-maternal medicine at Wake Forest in Winston-Salem, for example.

Unfortunately, both MVP and AFI are known to be poor predictors of actual AFV. One paper by Hughes et al. (2020) for example pits the two methods against each other on women with known reference AFV. Performance of the ultrasound measurements are stratified by the true AFV classified as low, normal or high. The AUC result for both methods are disappointingly low. The AUC for low and normal volumes is estimated as being between 0.53 and 0.59. For high AFV, minor improvement is seen with the AUC around 0.62 and 0.63. As a rule of thumb, an AUC of 0.5 is roughly equivalent to randomly selecting a test result, with a minimum acceptable AUC of 0.7 being suggested for a test to have utility (Hosmer et al. 2013).

A further complication is that an abnormal AFV is relatively rare. I’ve found estimates anywhere from 0.5-8.0% of pregnancies being affected. So what is the diagnostic value of an ultrasound reading indicating low AFV? The sensitivity for low AFV is quite poor, with Hughes giving point estimates of 15% and 7.69% for AFI and MVP, respectively. For specificity, Hughes gives point estimates of 97.54% and 99.08% for AFI and MVP. Plug the paper’s values into Bayes' theorem and prepare to be underwhelmed.

Management

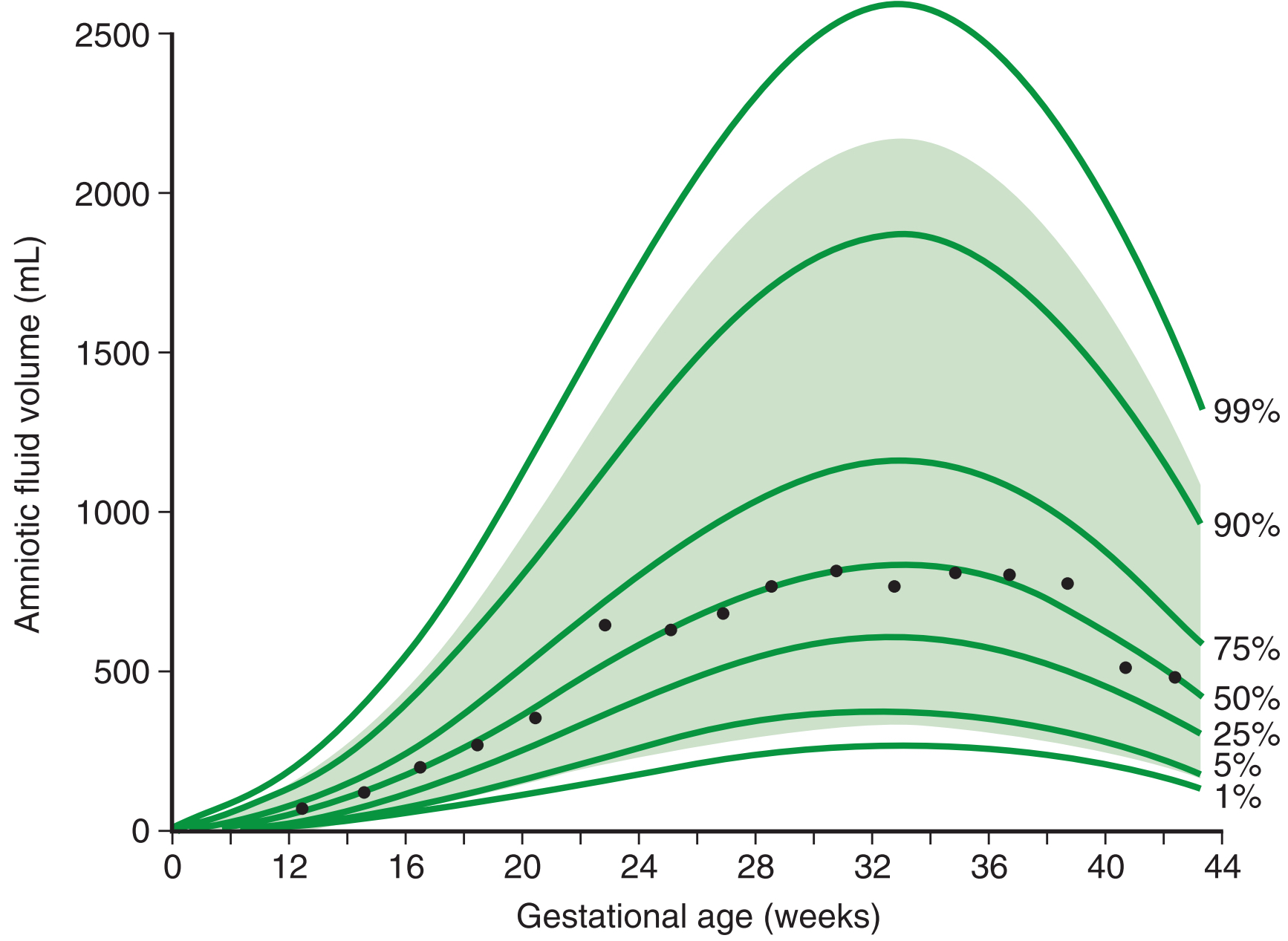

In short, we have a relatively infrequent medical condition that is looked for using a crude test with a very high false positive rate. Even if we allow for retesting after a few days, results are not necessarily “reassuring” towards the end of pregnancy due to the natural decline of AFV this far along. A study by Brace and Wolf (1989) estimates changes in amniotic fluid volume throughout pregnancy. What is interesting is that according to their measurements, AFV peaks between 32 and 34 weeks and then starts to decline. This paper is cited and reproduced in a few standard textbooks on obstetrics, so you would imagine providers are familiar with it.

This creates a risk if an AFV assessment is made after 34 weeks and the result is towards the low end. If a provider waits a few days, chances are that the reading will be similar or lower than the previous one for entirely natural causes. Note also the very high variation between readings as mentioned in Landon et al. (2020). Couple that with the recent trend of interpreting the ARRIVE study as demonstrating that there is no to minimal risk when inducing an early-term pregnancy (cf. Carmichael and Snowden (2019) for some good thoughts, and see the abstract of ARRIVE itself for selection criteria) and we have a recipe for otherwise unnecessary medical interventions. Even before ARRIVE, medical providers routinely felt that low AFV alone is a reason for offering inductions; see for example Schwartz et al. (2009) and Keilman and Shanks (2022) and many secondary citations in other papers on this topic. But induction is not as easy of a solution as it is made out to be. It can be more uncomfortable for the mother and rates of Ceasareans may be higher (though this is a bit disputed in the literature). Despite this, I’ve repeatedly encountered a borderline reading as being interpreted as indication for an expedited induction (within a day or less), even absent other issues or stress-tests.

Just to reiterate, these comments are regaring isolated oligohydramnios, that is, low AFV that is not a side-effect of some condition. Interventions for IO may be thought to prevent stillbirth in part due to an otherwise missed comorbidity such as fetal growth restriction, but the literature simply does not bear out the thought of this being accurate. Even for low AFV associated with a comorbidity, a relatively recent meta-analysis suggests basing practice decisions on the relevant comorbidity, and not the AFV results (Rabie et al. 20217).

Continuous EFM

A quick summary of the issue is available from the abstract to Knupp et al. (2020):

Continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) was first introduced commercially over 50 years ago with the hope of improving perinatal outcomes during labor. However, despite the increased use of EFM, definitive improvements in perinatal outcomes have not been demonstrated. Variance in tracing interpretation and intervention has led to increased rates of cesarean and operative vaginal deliveries and perhaps increased maternal and neonatal morbidity. Since its inception, several strategies have been developed in hopes of optimizing EFM and improving these outcomes.

Providers remain stubbornly committed to EFM despite the limitations and potential risks, while the promised improvements always remain somewhere beyond the horizon. Ironically, Knupp et al. continue their paper by recommending bluetooth enabled remote EFM solutions and the ever-popular “machine learning” to finally realize those longed-for improvements.

It seems hard to pick any particular study showing issues with EFM, because they are so common. This makes it somewhat difficult to understand why the use of continuous EFM remains so popular. For some references, see the aforementioned paper by Knupp. For a more colorful summary of the many issues with EFM, see Sartwelle and Johnston (2018). They seem to hit the nail on the head when showing that routine continuous EFM may be junk-science unwilling to die.

ACOG guidelines on EFM are hidden behind a paywall, but judging by the public FAQ’s statement on fetal heart rate monitoring, it appears as though they do not recommend routine continuous EFM. The American Academy for Nursing does not recommend routine EFM, and does not recommend using a routine EFM as part of admission since it is linked to higher rates of continued EFM utilization.

It seems to me that EFM is popular because it gives providers a sense of control. Continuous feedback gives the illusion of having immediate and continued access to a fetus' wellbeing. But that is precisely why this technology is problematic. Using crude tools during foetal monitoring has been shown to lead to unnecessary interventions, all of which have associated risks. During birth, patients are in a particularly vulnerable state — especially after prolonged labor — and any indication of risk to a fetus is likely to invoke an emotional response, as opposed to a rational or scientific one. This in turn can lead to poor outcomes that could have otherwise been avoided.

Concluding Thoughts

In my personal experience, obstestrics providers seem to be focus on narrow, short-term goals using outdated or unscientific methodology. Long-term outcomes seem less of a concern, as mother and baby are soon moved to another department after birth, so any subsequent negative outcomes aren’t “their problem” anymore. I don’t mean that this is done purposefully, but rather that the compartmentalization of hospital care and evaluation metrics for providers may inadvertently encourage this type of behavior. Additionally, I’ve been surprised several times at the datedness of a provider’s knowledge of the literature on a topic or what the result of a study was. In one case that readily comes to mind, a provider heavily pushed for a scheduled Ceasarean based on the results of a study she had collaborated on. Yet, when we asked for a reference and then looked up the study, the results actually suggested the opposite — expectant management — for our particular case. So it’s definitely worth to review treatment suggestions with your provider as we continue moving away from paternalistic models of care to one where patient and provider collaborate on finding the best treatment.

References

Brace, R. A., and Wolf, E. J. (1989), “Normal amniotic fluid volume changes throughout pregnancy,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Elsevier BV, 161, 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(89)90527-9.

Carmichael, S. L., and Snowden, J. M. (2019), “The ARRIVE Trial: Interpretation from an Epidemiologic Perspective,” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, Wiley, 64, 657–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12996.

Grobman, W. A., Rice, M. M., Reddy, U. M., Tita, A. T. N., Silver, R. M., Mallett, G., Hill, K., Thom, E. A., El-Sayed, Y. Y., Perez-Delboy, A., Rouse, D. J., Saade, G. R., Boggess, K. A., Chauhan, S. P., Iams, J. D., Chien, E. K., Casey, B. M., Gibbs, R. S., Srinivas, S. K., Swamy, G. K., Simhan, H. N., and Macones, G. A. (2018), “Labor Induction versus Expectant Management in Low-Risk Nulliparous Women,” New England Journal of Medicine, 379, 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1800566.

Hughes, D. S., Magann, E. F., Whittington, J. R., Wendel, M. P., Sandlin, A. T., and Ounpraseuth, S. T. (2019), “Accuracy of the Ultrasound Estimate of the Amniotic Fluid Volume (Amniotic Fluid Index and Single Deepest Pocket) to Identify Actual Low, Normal, and High Amniotic Fluid Volumes as Determined by Quantile Regression,” Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, Wiley, 39, 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.15116.

Keilman, C., and Shanks, A. L. (2022), “Oligohydramnios,” in StatPearls [Internet], Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562326/.

Knupp, R. J., Andrews, W. W., and Tita, A. T. N. (2020), “The future of electronic fetal monitoring,” Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Elsevier BV, 67, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.02.004.

Landon, M. B., Driscoll, D. A., Jauniaux, E. R. M., Galan, H. L., Grobman, W. A., and Berghella, V. (2018), Gabbe’s Obstetrics Essentials: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, p. 496.

Landon, M. B., Galan, H. L., Jauniaux, E. R. M., Driscoll, D. A., Berghella, V., Grobman, W. A., Kilpatrick, S. J., and Cahill, A. G. (2020), Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, p. 1280.

Levin, G., Rottenstreich, A., Tsur, A., Cahan, T., Shai, D., and Meyer, R. (2020), “Isolated oligohydramnios – should induction be offered after 36 weeks?,” The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, Informa UK Limited, 35, 4507–4512. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1852546.

Nabhan, A. F., and Abdelmoula, Y. A. (2008), “Amniotic fluid index versus single deepest vertical pocket as a screening test for preventing adverse pregnancy outcome,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Wiley, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd006593.pub2.

Patrelli, T. S., Gizzo, S., Cosmi, E., Carpano, M. G., Di Gangi, S., Pedrazzi, G., Piantelli, G., and Modena, A. B. (2012), “Maternal Hydration Therapy Improves the Quantity of Amniotic Fluid and the Pregnancy Outcome in Third‐Trimester Isolated Oligohydramnios: A Controlled Randomized Institutional Trial,” Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, Wiley, 31, 239–244. https://doi.org/10.7863/jum.2012.31.2.239.

Rabie, N., Magann, E., Steelman, S., and Ounpraseuth, S. (2017), “Oligohydramnios in complicated and uncomplicated pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, Wiley, 49, 442–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.15929.

Sartwelle, T., and Johnston, J. (2018), “Continuous Electronic Fetal Monitoring during Labor: A Critique and a Reply to Contemporary Proponents,” The Surgery Journal, Georg Thieme Verlag KG, 04, e23–e28. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1632404.

Schwartz, N., Sweeting, R., Young, B. K., Schwartz, N., Sweeting, R., and Young, B. K. (2009), “Practice patterns in the management of isolated oligohydramnios: a survey of perinatologists,” The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, Informa UK Limited, 22, 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050802559103.